Japan’s music differs vastly from Western music, both in its sound and the rich history behind it. While many of you might be familiar with J-pop or game music, the real beauty lies in the centuries of history and culture where the true identity of Japanese music lies.

Japan witnesses a plethora of wind, string & percussion instruments, and each one is closely linked with the traditions of the regions they developed and evolved. These instruments give Japanese folk music its exquisite and distinct flavor

Today, we’ll introduce you to seven traditional Japanese String Instruments that have graced the Imperial Court music in the 5th century and have survived their way to modern-day rock & pop.

Here’s a list of 7 famous Japanese Stringed Instruments you should know!

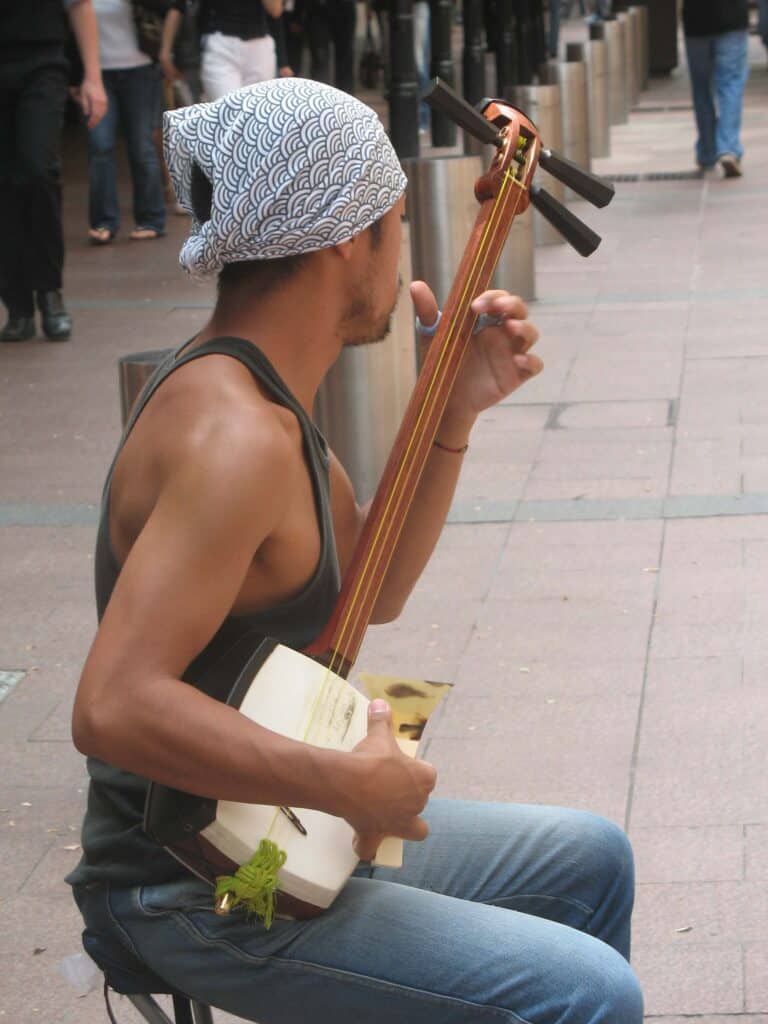

Shamisen (三味線)

Shamisen literally means “three strings” in Japanese. The instrument is believed to have been brought into Japan during the Edo period (1603 – 1868) via the Chinese Sanxian and Okinawan Sanshin.

Although both Sanxian and Sanshin used to be covered in python skin, the Japanese started using dog and cat skin for their instruments. However, the use of these skins gradually declined and was replaced with plastic.

Its body (dō) is made from 4 pieces of hardwood joined together to form a square frame. On either side, stretched dog or cat skin is glued to form a drum-like body. The neck (sao) consists of 3 or 4 pieces of wood perfectly fit together and houses three silk or nylon strings. It’s similar in length to a guitar neck but has no frets or fretboard.

A distinct feature of the Shamisen is that the first two strings rest on the brass nut, but the third string runs over a cavity on the nut, which is purposefully done to create a characteristic “buzzing” timbre. The instrument is played with a large triangular plectrum, called a “baichi,” which can be used to pluck the strings or hit the body to add percussive effects.

Shamisen has been historically popular both as a solo instrument and as an accompaniment at Kabuki and Bunraku theatre performances. Besides its closely-knit relationship with traditional folk music (minyo), it has evolved and adapted to suit modern styles & genres.

Contemporary musicians have brought more individuality & personality into their music using the Shamisen for a variety of genres from rock, bluegrass, jazz and even metal. It was even featured in the 2016 movie Kubo and the Two Strings, where the main character is seen performing in his local streets.

Koto (琴, 箏)

Regarded as Japan’s national instrument, the Koto is a large plucked zither similar to the Chinese Guzheng. It’s fascinating the Koto remained an instrument of the Japanese Imperial Court for a long period since it first appeared during the Nara period (710-794).

This changed in the 17th century when one of the court’s Koto musicians decided to teach Koto to a blind musician by the name of Yatsuhashi Kengyo. Yatsuhashi is credited for developing a new style of Koto and expanding the repertoire beyond the limited selection of songs. He is now known as the “Father of Modern Koto.”

Kotos have existed in a variety of styles and types, but the most common one uses 13 strings stretched over movable bridges & is made of Kiri wood. There are variants with 17 strings (bass Koto) or even more than 20 strings which have gained popularity recently with the advancements in playing styles & the influence of Western pop music.

Traditionally, Koto has been associated with romantic music due to its soothing harp-like sound. However, modern players are finding their places in jazz, pop & fusion music, with some notable players being Reiko Obata, Michiyo Yagi & Miya Masaoka, among others.

Sanshin (三線)

Like Shamisen, Sanshin also means “three strings” in Japanese. Similar to Shamisen, it bears close resemblance to the Chinese instrument Sanxian, but with apparent differences.

Sanshin is the national instrument of Okinawa (one of the Japanese islands) and has a body made of snakeskin, as opposed to cat or dog skin on the Shamisen. Another major point of difference between them is the pick. The Shamisen has a large triangular pick, whereas the Sanshin has a finger-like pick resembling a large hollow fang, which the players wear on their index fingers and pluck the strings.

The music of Japanese islands is very different from that of the Caribbean, and the Sanshin lies at the heart of Okinawan folk music. Besides family gatherings, weddings, and festivals, the instrument has been an integral part of the Ryukyu culture, where it’s often associated with Deities and is celebrated as an instrument of legacy.

Sanshin sounds like a banjo but has a very characteristic warm timbre to it. If you ever visit Okinawa, don’t forget to experience the beauty of this traditional instrument. You might find children as young as 2 years old or elders over 100 years playing the instrument.

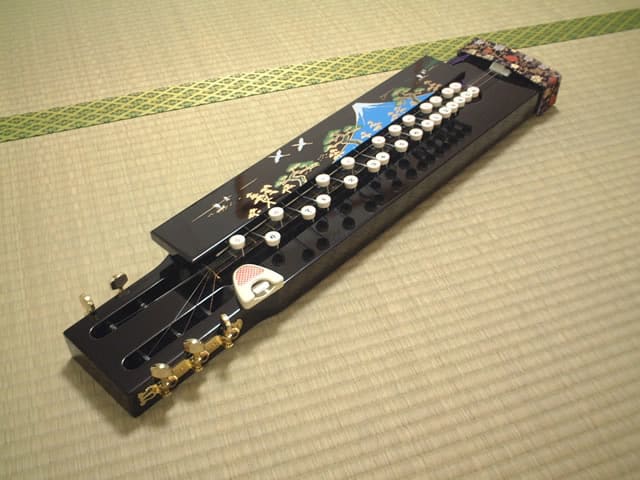

Taishogoto (大正琴)

Taishogoto is a much more recent Japanese Stringed Instrument than some others on this list. It was developed in 1912 (during the Taisho period) by Goro Morita in the city of Nagoya, hence the name “Nagoya Harp.”

The inspiration behind this unique variation of Koto is typewriters – Yes, you heard that right!

Morita was influenced by Western instruments. He later came up with the idea of combining the mechanics of conventional string instruments with typewriter-style buttons to change the notes. The Taishogoto consists of a long acoustic sound box with metal strings on top and numbered typewriter-like keys spread across its length.

The players strum the strings with a pick on one hand while pressing the keys with the other hand to “fret” the notes. The simple mechanics and the ability to produce notes from the Western 12-note scale make it very accessible and easy to play for anyone.

The Taishogoto is played in a variety of modern genres, from children’s music to large groups of musicians playing pop music. It’s also a precursor to the Indian instrument Bulbul Tarang & the German Akkordolia.

Biwa (琵琶)

Biwa is another popular Japanese String instrument with a long history & cultural significance. It’s derived from the Chinese Pipa and bears a strong resemblance to it – pear-shaped body, short neck, and four strings. However, it differs greatly in terms of the sound and how it’s played.

Biwa typically consists of 4 or 5 strings and 4 to 6 frets, much less than the Pipa. The tuning varies greatly with the type of Biwa, and the instrument is played with a large plectrum called Baichi. Plectrum size and materials also contribute to the sound texture.

What’s interesting is that the entire body of the instrument (including the neck) is carved from one piece of wood. Also, the frets are much higher than some other common lutes, and the pegbox is bent backward, giving it a distinct appearance. There exist more than seven types of Biwa which differ in size, tunings, and the music they are used in. The most famous ones are the Gagaku Biwa, Satsuma Biwa and the modern Chikuzen Biwa.

The Biwa has traditionally been used in Japanese court music (Gagaku) or as an accompaniment in storytelling and folklore recitals such as The Tale of the Heike. However, despite the royal patronage and vast popularity, Biwa music has been on a decline since the Pacific War. As a result, a traditionally constructed Biwa is hard to find these days, so if you do see one, make sure to cherish it!

Here’s another interesting fact – Lake Biwa (Biwako) bears its name due to the resemblance of its shape with this traditional Japanese instrument. Also, the Japanese Buddhist Goddess Benzaiten (Benten) is often depicted holding a Biwa.

Tonkori (トンコリ)

The Tonkori is a Japanese musical instrument developed in Sakhalin and played by the Ainu people of Hokkaido and other Northern regions. The instrument is fretless and is made from a single piece of Jezo spruce wood.

Unlike many other string instruments, the strings on the Tonkori are not fretted (or pressed) and are played open. The instrument commonly has 5 strings, although some variations can have more or less.

The strings are usually made of gut or vegetable fiber and are tuned in a reentrant tuning (alternating order of pitch), which gives it very distinctive sound and tonal qualities. This uniqueness also extends to the songs and dances the Tonkori played in.

Tonkori songs traditionally don’t have a beginning or end and are often inspired by natural beauty, such as birds and weather. However, the use of the instrument has declined in recent decades due to the forceful homogenization of the Ainu identity and language with the Japanese society.

Despite these struggles, the Tonkori still sits at the heart of Ainu music, and modern musicians like Oki Kano (OKI) are reviving the instrument by combining traditional music with electronica and reggae music.

Kokyu

Among all the Japanese string instruments, the Kokyu is the only one played with a bow. The instrument looks very much like the Shamisen, albeit much smaller.

Like the Shamisen, the Kokyu bears its origins in Okinawa, where it’s called Kucho. The main difference between them is that in Okinawa, the body is round as opposed to the square shape in mainland Japan.

It typically consists of 3 strings and is played upright with a horsetail hair bow. The construction and playing style is reminiscent of the Chinese Huqin instruments.

Kokyu has been prominent in the Sankyoku ensemble, where it’s played as a vocal accompaniment along with the Shamisen and Koto. However, more recently, the Japanese wind instrument Shakuhachi is used in place of the Kokyu.

Several recent developments, notably the addition of a string to expand the range, have proliferated its appeal to a wider audience. As a result, the Kokyu has experienced occasional usage in modern jazz and blues music.

Conclusion

Some of these Japanese string Instruments might be considered archaic by the newer generations, but they are still an indispensable part of Japanese music and are used in festivals and concerts all over the country.

These instruments are one of the most valuable tools that give us an insight into the thousands of years of authentic tradition. The importance of culture is evident from the fact that many of these instruments almost went extinct and have been revived thanks to the efforts of their respective communities.

If you ever visit Japan, don’t forget to witness the beauty of these Japanese string instruments. And as always, thanks for reading!

I’m Pranshu. I’ve been a passionate guitarist, keyboardist, and music producer ever since I got my hands on a keyboard as a small child.

With Harmonyvine, my goal is to share tips and knowledge about music and gear with you. I also enjoy recording music and guitar covers, which you can check out on my Instagram page.

Thank you! I remain intrigued by similarity of European & Asian stringed instruments. The use of the vibrating string across vast distances is fascinating.

The bird flys away, but the rat will hunt at night